In 1930 the woman who called herself Mrs Hill caught the Old Trans across the Nullarbor. She sat with a notebook propped on her knees, her suitcase, typewriter and thin swag slung in the rack overhead, revelling in the train’s front-stall view of the weird and mournful wilderness all around.

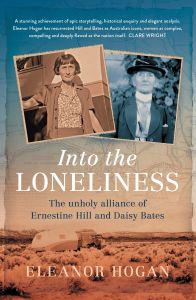

Sometimes books come into your life that you think you will like, that you want to like, but that simply do not live up to expectations. Into the Loneliness: The Unholy Alliance of Ernestine Hill and Daisy Bates was one such book. Most of the problem lay with Hill and Bates themselves. I simply couldn’t like them.

I felt like I should have though.

I was a single woman for a long. A woman who also chose to remain childless (like Hogan herself). I understood all three women’s desire for freedom and independence, almost perfectly. But as I slogged my way through this book, I realised that even though I may understand where they’re coming from, I did not actually like or admire Hill and Bates very much.

My friendship, or approval, is not required of course, but it is very difficult (for me) to continue on with a book about people that I’m struggling to respect. Their experiences of the outback at this time in history are fascinating, but the petty bickering and jealousies, self-interest and self-deception were tedious to read about.

Bates may have had part of her heart in the right place, in trying to record and preserve the language and culture of the Aboriginal groups that she lived with. But it was always on her terms, and her terms only. Full-blooded Aboriginals were the only ones deemed worthy of her attention, and she was only doing so thanks to her belief that the Aborigines were dying out, and this was her last act of anthropological mercy (or her last chance at fame) before they did so.

She (Bates) attracted derision not only because of her idiosyncrasies, her anachronistic Victorian attire and high-handed ways, but more seriously because of her active loathing of mixed-descent children and her scandalous reporting on Aboriginal cultural practices.

Hill made up stuff to suit her own purposes, as did Bates.

The phrase ‘poetic licence’ is often used by others to describe their work. Controversial embellishments obviously helped them to sell copy. Bates’ claims about infant cannibalism have been roundly condemned, even during her own lifetime. It is easy to say that her paternalistic attitude and defence of colonial practices were simply of her time, yet many from her time did challenge these views. Not enough, I grant you, but an alternate viewpoint was available. She didn’t have to take that road.

Bates’ determination to record as many words, in as many First Nations languages as possible, is, however, worthy of note. The Digital Daisy Bates project is an attempt to collate over 23 000 pages of word lists compiled by Bates. This is an extraordinary resource.

By 21st-century standards, I often found Hill’s style twee and sentimental, her outlook and preoccupations dated, sometimes racist and offensive; I cringed equally at her purple prose and patronising descriptions of ‘exotic others’. But I was struck by Hill’s facility as a journalist and travel writer in straddling the boundary of popular and middle-brow writing to communicate the diversity of experience in remote Australia to metropolitan readers during her era.

I wasn’t always comfortable with Hogan’s presence in this story, but I was duly impressed by her extensive research and passion for this project. We do need committed writers and meticulous researchers to bring these stories and histories to life. The Pitjantjatjara glossary, map of Australia, and extensive notes and references at the back, are all signs of Hogan’s hard work and due diligence. She was an excellent choice as winner of the 2019 Hazel Rowley Literary Fellowship for her proposed biography of Ernestine Hill and Daisy Bates.

I acknowledge that I am not currently in a good position to take the time to carefully read and truly appreciate a thorough, detailed biographical work, about two people I am only moderately interested in spending time with. Narrative non-fiction is more my style at the moment.

Although one thing I have come away with after reading this, is that I have no desire to read anything else written by Bates or Hill. My Love Must Wait was more than enough Hill for one lifetime, and I am glad that Hogan has done the hard yards for the rest of us in preparing to write this book. I call that taking a BIG one for the team!

Note: I only read half the book. I skimmed some sections around the middle. This was a DNF.

Book: Into The Loneliness | Eleanor Hogan ISBN: 9781742236599 Publisher: NewSouth Books Publication Date: March 2021 Format: Trade Paperback

| This post was written on the traditional land of the Wangal clan, one of the 29 clans of the Eora Nation within the Sydney basin. This Reading Life recognises the continuous connection to Country, community and culture of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. They are the traditional custodians of the lands, seas, and skies on which we live and they are this nations first storytellers. |

I can understand your reaction to this – whatever the motivations of these women were, their actions seem flawed and dangerous.

LikeLike

I kept saying to myself ‘they are products of their time’. But really it was more than that. We are all flawed human beings, but I found their behaviour bordering on the narcissistic. Which can be fascinating to observe…from afar, but not always edifying.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve always thought of Daisy Bates as one of those people we need to know about, but a quick scan of Wikipedia is enough for most of us.

Still, as you say, ‘hats off’ to Hogan for doing all that research. Scholars of that period will be grateful to her.

LikeLike

You’ve just reminded me that I meant to check what my old Australian Writers book had to say about both women. I’m curious to see how they were viewed in the 1950’s…

LikeLike

The team appreciates it!

Striking Bates and Hill from my reading list.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I may still have a Hill non-fiction on my ipad reader, that I may dip into one day. But I’m certainly in no hurry.

LikeLike

I do know that feeling of wanting to connect with a book or an author’s writing in a way that I seem unable to. Sometimes returning to it/them later on (years later) can help but in this case it doesn’t seem as though it would help you.

LikeLike

Yeah, I’m not sure this will be a case of bad timing either. I’ve passed it into a friend, so I’ll be keen to get her input – hopefully over a coffee in sept when this latest lockdown is over!!

LikeLike